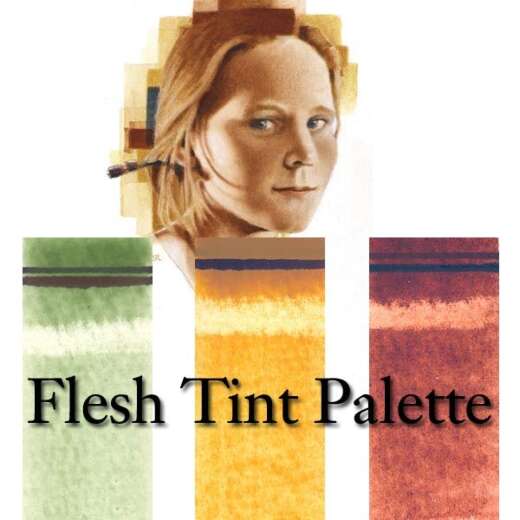

Roger de Piles on Oil Painting—Flesh Tones

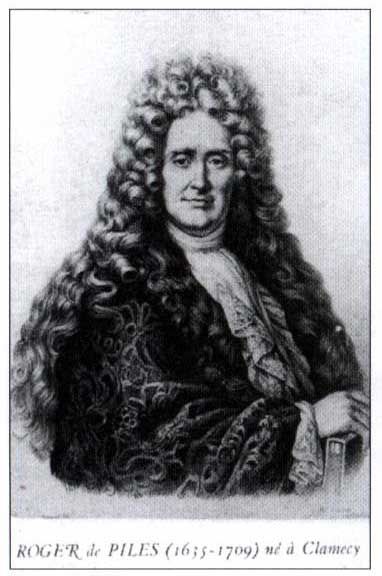

Roger de Piles (October 7, 1635–April 5, 1709) was an art critic, theorist, and collector whose significant contribution to aesthetic theory rests on his Dialogue sur le coloris (“Dialogue on colors”), in which he initiated his famous defense of Rubens in an argument started in 1671 by Philippe de Champaigne on the relative merits of drawing and color in the work of Titian. In 1668, he published an annotated translation of Charles-Alphonse Dufresnoy’s De Arte Graphica that greatly influenced the aesthetic discussions of the day. De Piles later published several painting manuals that became essential resources for oil painters in the following centuries.

Roger de Piles (October 7, 1635–April 5, 1709) was an art critic, theorist, and collector whose significant contribution to aesthetic theory rests on his Dialogue sur le coloris (“Dialogue on colors”), in which he initiated his famous defense of Rubens in an argument started in 1671 by Philippe de Champaigne on the relative merits of drawing and color in the work of Titian. In 1668, he published an annotated translation of Charles-Alphonse Dufresnoy’s De Arte Graphica that greatly influenced the aesthetic discussions of the day. De Piles later published several painting manuals that became essential resources for oil painters in the following centuries.

The following is a translation by the editor of chapter 4 (incomplete) of Roger de Piles’ Les Elémens de Peinture Pratique.

CHAPTER IV. This species of painting is modern in comparison to others, but it has considerable advantages in that it mimics nature more perfectly, by both the union and mixing of its colors, by the force and vivaciousness of its colors, as well as by the beauty and the delicacy of its execution. It can do everything in its effect when viewed closely; it gives you time to finish and soften anything you want, and to make changes with ease and edit what you do not like, and when it is not entirely clear what is already accomplished: Finally, it is unique to the largest and the smallest. There is no doubt that it would be the most perfect of all ways to paint if the colors did not darken later, but they always increasingly turn brown and incline toward a yellow-brown, which comes from the oil with which all colors are crushed and incorporated. The most considerable convenience of this work is to see, first of all, what is being done as it should appear in the painting because the colors do not change in oil after drying as those in tempera; in addition, oil painting has the merit to resist moisture when the color is well dry, thereby lasting a very long time. The reflection or shining of its colors is still a considerable disadvantage in that it prevents their effect unless the painting surface is not exposed to direct light, so they can be placed in all large exhibitions, with which light is favorable.

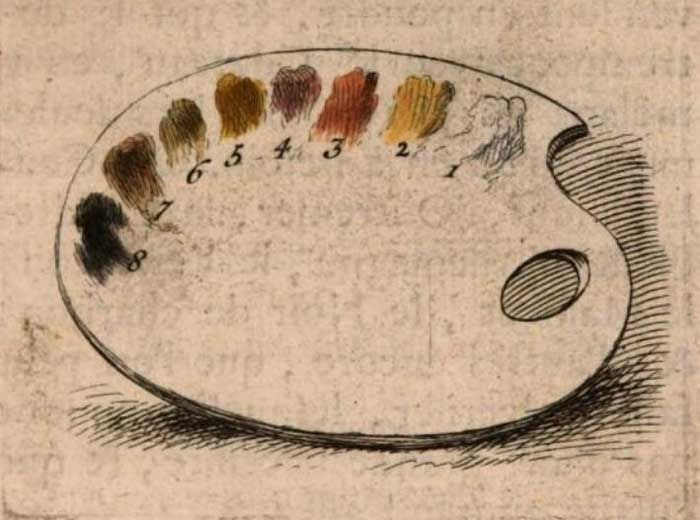

Arrangement of colors on the palette. As we have seen before, we arrange the shades of colors in ranges at the top of the palette, observing to place the lightest colors nearest to the thumb and in small piles separated from each other. With the colors placed in order in rows, we take the palette in the left hand and support it on the thumb in a hole made for it at the bottom. In the same hand, we hold the brushes that will be used. The same hand can also hold the finger stick (mahl stick—Ed.) or the hand support, and the torch brush, which is a small piece of cloth used to wipe the ends of brushes, and the knife, which mixes the colors on the palette when they are needed. Oil painting usually uses eight principal colors: almost all others are derived and are composed of a mixture of these. They are arranged in a range roughly this way. 1. White lead. 2. Yellow ochre. 3. Brown red. 4. Lake. 5. Stil de grain. 6. Green earth. 7. Umber. 8. Bone or ivory black. These are the names of the eight colors and the order in which they are almost always placed on the palette. See fig. 8. These colors are sold crushed, and to keep long and clean, they are kept in a portion of a pig bladder, which makes it handy and flexible by rubbing with a bit of water, and in small packages bound with a string. To make use of the color, it is withdrawn through a small hole made with a big pin, and by pressing the package, you can bring out roughly the amount that must be used onto the palette. Other colors are sold in powder, and that temper with the knife on the palette by mixing with a bit of oil, only when needed. These colors are ultramarine, German blue ash (azurite), vermilion, massicot, carbon black, and others that are not of great importance and, through use, learn to know.

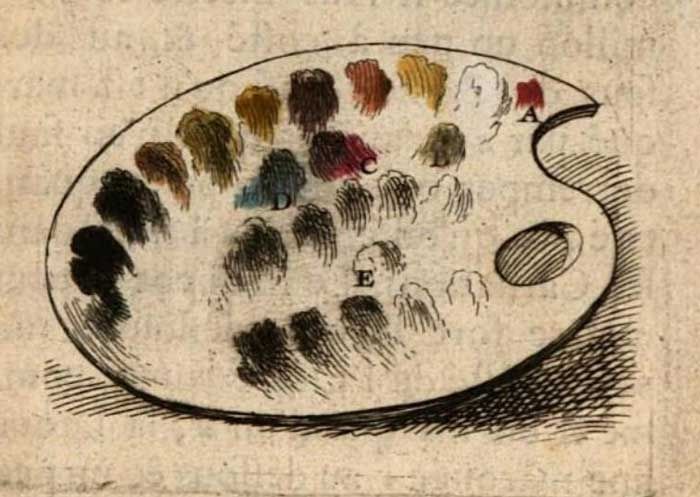

Fig. 9 Of tints and mixtures of colors. It is impossible to give rules on the mixture of colors, but with use and a little practice, you can learn more than from long speeches. Still, to provide those who are starting to paint all the facilities that depend on us, we recommend copying their first head from one that is beautiful, fresh, and well-colored; this is the best advice we can give them because good beginnings leave long time impressions in the mind of the things copied. There are painters who, having started to copy in gray tones, do so for their remaining lives. Suppose it is a question of copying a head of fresh and live flesh tones. Before beginning to paint, all the significant shades needed to imitate what you want to copy should be placed on the palette with the tip of the knife. The shades are made by taking a little of the main colors at the top of the range with the tip of the knife and mixing them together until we have found the shades we seek. The natural flesh tones have their light, shadows, and reflections or halftones, but to imitate these three degrees, the painter mixes the colors, making different shades on the palette. They arrange them to each other, below the eight principal colors, always putting the brightest nearest the thumb holding the palette: as we have already said, these shades should be mixed with the knife, which would be the wrong way to do with a brush. Returning to the proposed head: it has its light, shadows, and halftones. To imitate the light, there are usually four light shades. The first is composed of white and a little yellow; the second, white, vermilion, and lake, the latter two being added in very small quantities. The third is like the second, by putting a little more lake and vermilion; the fourth, like the third, by mixing a little more of the last two colors. It may be here that we want to make a fifth shade darker than the latter. These shades are set in a single row, the halftones and shadows placed underneath. There are usually three halftones: make the first by mixing white with some yellow, some lake, and a little ultramarine. The second, like the first, make by diminishing the white and increasing the three others. The third, as the second, make by further decreasing the white and similarly increasing the three other colors. The shades for shadows start from the halftones: just make two. The first consists of lake, yellow ocher, and ultramarine, making sure to use yellow in larger quantities than the other two. The second is best with stil de grain, lake, and a little bone black. Let’s now show a summary of the arrangement of all these colors on the palette, as seen in fig. 9. The eight main colors occupy places at the top of the palette. As we have already said, the eight colors are white lead, yellow ocher, brown red, lake, stil de grain, green earth, umber, and bone black; you can add carbon black that, for some uses, is better than others. Place the shades to paint the flesh tones below these principal colors and arrange them in two rows: those for light values above and those for halftones and shadows below, always observing to put lighter colors nearest the thumbhole. Between these two rows, putting a little yellow is worthwhile because you will need it often, and it is more convenient to take it from this place with a brush while painting than to blend it with the hues from which it was prepared. It is marked by an E in figure 9. For the other colors, such as fine lake and vermilion, ultramarine and massicot, put them where you want; however, for more convenience, put the vermilion next to and below the white, as seen in A, all it takes to become saturated is a tiny amount, and that has little business in flesh tones. The massicot might well be placed below and next to a bit of yellow ocher, as in B; the fine lake is marked C, below and a little beside the coarse lake; and ultramarine in the place marked D. We should not pretend that all these shades are in the places they should be to produce the effect we desire and make the head exactly as the original we propose to imitate. They are made up only to facilitate the next mixture we should paint with. Because when something does not tint the color you want, we must put the brush aside and what it lacks and finally make it as it should be, increasing or decreasing one or another color. As regards the mixture of colors and the effect they produce with each other, there is little that experience cannot teach you. I will warn you, however, that unless umber can serve you, it spoils the other colors, and it is good only to make brown backgrounds and brown draperies and to use in a few places. When you have some cloth or some other thing to paint, which has its light, shadows, and halftones, they must be prepared on the palette with four or five shades, mixing with the primary color on which you wish to paint drapery, a light color for the light, and a brown color for the shadows and that by degrees. It should be noted, as has already been said, that the lightest hues on the palette place nearest to the side of the thumbhole, and the other colors then away as they become darker. Manner of sketching and dead-coloring a painting. As an oil painting is usually painted on canvas or on walls where the picture is brown, one begins to sketch by tracing the outline of figures and draperies with a pencil made of white chalk, which can be easily erased with a white cloth or a sponge moistened with a bit of water. Then retrace the same contours with a hue that is the local color of each thing: for example, flesh tones; lake is used with a bit of green earth or umber, or some other color that serves the union, which promptly dries and that is not incompatible. Retrace the contours of similar-looking draperies with one of their hues: then complete the void with other colors, the lights, and shadows, and finally make the underlayers of the picture—the so-called proper dead-coloring (I will use the term “underpainting” interchangeably in this text—Ed.). Let this painting dry, after which we can finish with the same or lighter or darker colors. Start from the top of the picture, from left to right, as when writing, if the painting is very high on rollers or built if it is mounted on stretcher bars. We can make an observation here that uses specific oil colors in the underpainting with common colors, sparing those colors at too great a price. For example, when finishing a drapery with a fine lake, one can use common colors in the underpainting. Similarly, a drapery that we must finish with the best ultramarine can be started in underpainting with the most common ultramarine. Finally, instead of ultramarine in the first hue shade and even in halftones, we can use willow charcoal, which is a little bluish, or bone black in the underpainting, and then finish with ultramarine, but the practice is not so good, and the tints not so fresh. This picture underpainting serves only to cover the canvas with colors and to see the effect. Still, it must be done correctly, and all colors must be as well placed as possible: for this purpose, the design must be well fixed before starting the picture. For if one puts a finishing brown on light, unlike red on blue, or colors very different from one on another, the last layers still lose their sparkle upon drying. When one wants to make changes, it requires repainting several times to give more substance to the last color, which must remain. The fact that some colors seem fresh at a point or do not retain their long-time beauty and brilliance sometimes creates turmoil for the painter. Placing colors together, he finds that some alter and corrupt others, dulling, so to speak, their edge and their liveliness. That is why we must use them cleanly and in layers, as we just said, the primary colors each in their place, without blending with a small paintbrush or with a wide brush, and to preserve individuality between the two; finally, we unite rather than by applying friction. Another critical attention is not to mix clashing colors or can corrupt others with their extreme heaviness, such as black, or their poor quality, such as lampblack, verdigris, and a few others that we must use by hand if one is to use force. And even when it is necessary to give more power to some parts of a painting, you must wait until it is dry if you want to apply colors that can harm the paint layers. Some painters do all these observations; nevertheless, they are necessary to keep the beauty of colors. For those who work with judgment, every color is applied with small strokes without haste, the flesh tones they make thicker, covering and recovering several times, what painters call well thickened. The oil colors have the advantage of being able to mingle easily with the handling of the brush, but it is feared that with the strength to torment colors, you do not lose their freshness, especially in flesh tones, and that they do not become dirty and earthy. That is why in order not to spoil the shades of colors by drowning them in each other, some painters end up breaking up individual shades, which admirably succeeds in masterworks. To avoid this problem, there are two things to observe: the first is to get accustomed to painting and blending colors promptly and with the lightness of brush, with strength, if possible, not pass the same place twice. The second is that, after so slightly mixing colors, we must take care not to brush over pure and fresh colors, which are correct for the places where they are placed, and which are the same tones as those that have already been painted and mixed underneath. To learn how to paint with strength, there is nothing better to do than to copy a few works of Correggio and Van Dyck for the lightness of brush strokes and others, Paul Veronese and Rubens, for the purity of colors. Color applied over a painting, when it is pure, without touching others underneath, retains its brightness over time. That is why we disapprove of the use by a few painters who finish their pictures over the underpaintings by putting some color and much oil as if glazing; sometimes using oil of turpentine to make the color more easily: it is true that this way expedites the work, but it is a dangerous practice to follow. Indeed, these pictures do not seem to be more than colored fog without vivacity because too much oil, mainly turpentine, absorbed and killed the colors. It is unnecessary to point out that, to paint with good grace, one must use a brush as long as possible and be right in his seat; however, without constraint and at a reasonable distance from one’s work; one paints much more freely. On the contrary, there is nothing more than bad grace to use a short brush too close to the nose, as they say, on one’s work. |

Additional Reading

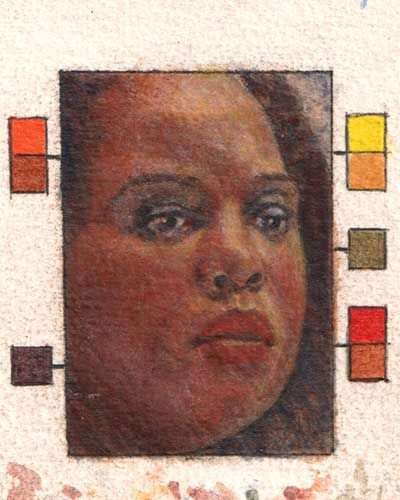

Read more about Roger de Piles’ flesh tone palette from Les Élémens de Peinture Pratique and setting the 17th-century flesh tone palette using Rublev Colours Artists’ Oils.

Order the Roger de Piles Flesh Tone Palette

Reference

Roger de Piles. Oeuvres Diverses de M. de Piles de L’Académie Royale de Peintute et Sculpture. Tome Troisieme. Contenant Les Elémens de Peinture pratique. A Amsterdam et a Leipzig, Chez Arkstée & Merkus, Libraires. Et Se Vend a Paris, Chez Charles-Antoine Jombert, Libraire Du Roi Pour l’Artillerie & Le Génie, à l’Image Notre-Dame (1767). Tome III. Elémens de peinture pratique, avec l’idée du Peintre parfait: De Peinture. I. Part. 97–113.