A ground serves as a preparatory layer on a support like canvas or wood, creating a suitable surface for painting. It enhances paint adhesion, controls absorbency, and influences the texture and visual qualities of the artwork.

Rembrandt's Painting Grounds: Techniques and Insights for Artists

Grounds, the preparatory layers applied to painting supports, play a vital yet often overlooked role in painting. For Rembrandt van Rijn, grounds were more than a surface—they actively participated in the dramatic interplay of light and shadow that defined his works. This article explores the materials, methods, and historical context behind Rembrandt’s grounds, drawing from technical analyses and historical treatises, including those by Theodore Turquet de Mayerne and Willem Beurs. By examining these foundations, artists can glean valuable insights into materials, techniques, and practices to refine their craft.

Grounds in the Dutch Golden Age: Panel and Canvas Preparation

The color and texture of the ground significantly influence the final visual and technical outcomes of a painting. The ground’s hue dictates the painting technique: a white ground supports a progression from light to dark. In contrast, a darker ground necessitates working in reverse, with light accents typically added in the final stages. Analysis of paintings where the ground remains visible indicates that Rembrandt often utilized a middle-tone ground. This choice allowed him to establish the overall balance of light and shadow early in the process, with the ground acting as a tonal intermediary. This approach facilitated efficient execution while simultaneously enhancing the chiaroscuro effects central to Baroque aesthetics.

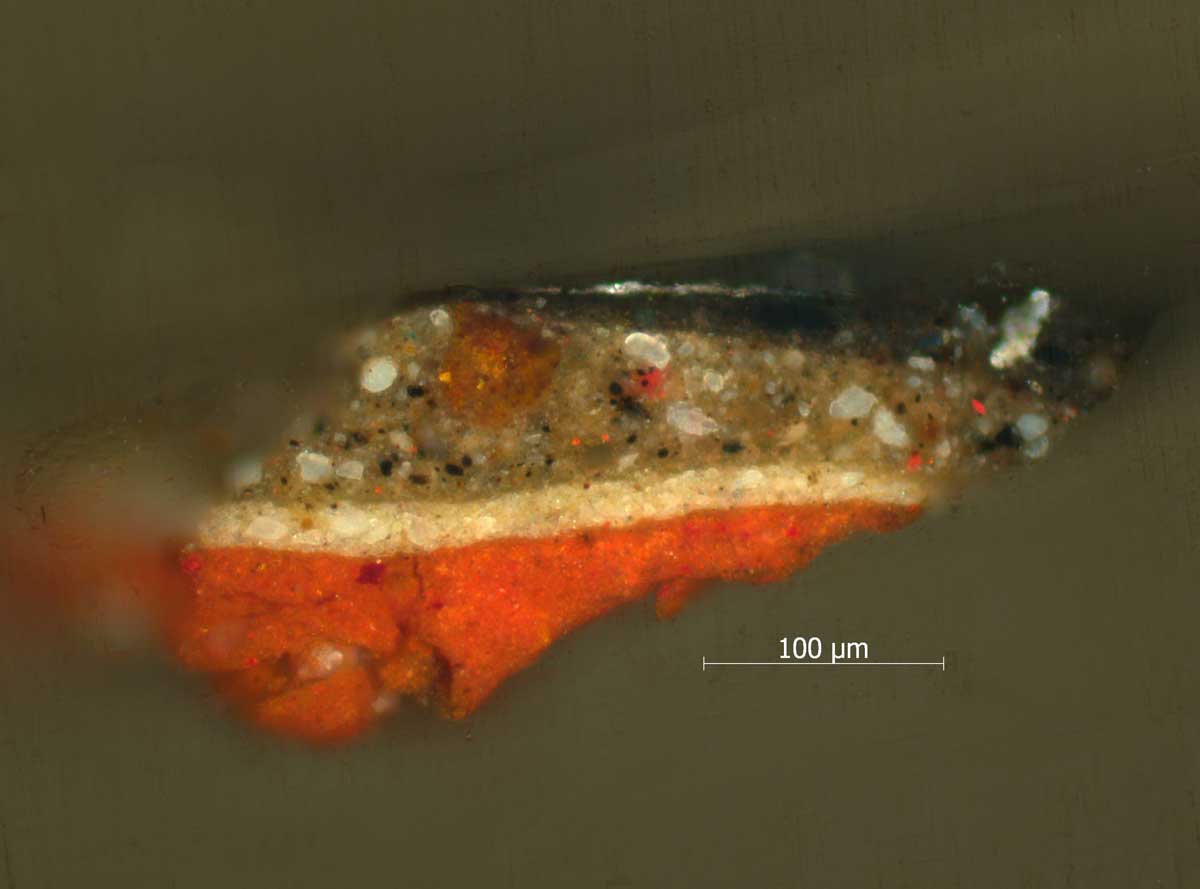

This image, captured with light microscopy at 10x magnification, illustrates the typical ground preparation used for wooden panels. The base layer consists of white chalk, topped with a lightly colored imprimatura, over which a dark paint layer is applied. This combination provides a smooth, absorbent surface while contributing to the tonal harmony of the artwork from the painting Musical Allegory.

Rembrandt, Musical Allegory, dated 1626, oil on panel, 63.4 x 47.5 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Rembrandt’s early works, primarily executed between 1626 and 1631, were painted on panels. The preparation of these panels followed a standardized process described by de Mayerne in his Pictoria, Sculptoria et quae Subaltemarum Artium (1620). He outlines:

“For [a ground on] wood, first coat it with... glue and chalk. When it has dried, scrape and make it even with a knife, then apply a thin layer of lead white and umber.” (de Mayerne, 1620)

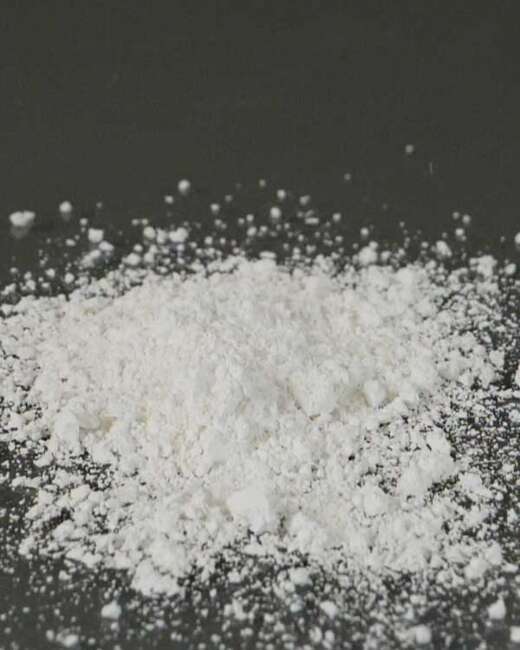

This method created a thin, chalk-glue base layer to seal the pores of the wood, followed by a light oil-based imprimatura of lead white mixed with umber. This imprimatura added a yellowish tone to the surface, blending seamlessly with the composition’s tonal balance. The thinness of the chalk layer differed from Italian traditions, where multiple gesso layers were applied and built up to a thick layer. Rembrandt's panels are often primed with a chalk ground, on top of which a thin light-colored layer of primer, called primuersel, was added.

Key Takeaways for Artists

The chalk-glue layer provides a smooth, absorbent surface.

A warm-toned imprimatura establishes the overall balance of light and shadow.

The Shift to Canvas: The Evolution of Double Grounds

Rembrandt transitioned to canvas as his primary support after 1631. The preparation methods for canvas grounds, also detailed by de Mayerne, involved:

“Having stretched the canvas tightly, apply glue made from the remains of leather or size, which should not be too thick (it is assumed that you have first removed any threads that might be sticking out). When the glue is dry, prime rather lightly with brown-red or red-brown from England. Let it dry, and make it smooth with pumice stone. Then prime with a second and last layer of lead white, [and] well chosen charcoal. Small coals(?) and a little umber earth to make it dry faster. One can give it a third layer, but two is all right, and [such a ground] will never break, nor split.” (de Mayerne, 1620)

This double-ground technique layered a reddish-brown base with a lighter topcoat of lead white mixed with pigments such as umber or charcoal black. These layers created a reddish-gray surface that harmonized well with Rembrandt’s chiaroscuro effects.

This image, captured using light microscopy at 20x magnification, highlights the double-layer ground commonly employed for canvases. The preparation features a reddish or brown base layer beneath a lighter topcoat, offering an ideal surface for tonal variation and strong adhesion.

Rembrandt, Bellona, dated 1633, oil on canvas, 127 x 97.5 cm, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Willem Beurs corroborates this technique, recommending a “greyish brown ground made with lead white and umber, applied thickly in oil” for portrait painting (The Large World of Small Painting, 1692). For landscapes, he advised a lighter ground using lead white and black to create a gray hue.

Quartz Grounds: A Unique Innovation in Rembrandt’s Workshop

After 1640, a distinctive type of ground emerged in Rembrandt’s studio: quartz-enriched grounds. These grounds, consisting of finely ground sand mixed with clay minerals such as illite, kaolinite, and sometimes muscovite (mica), accounted for approximately 50–60% of the ground’s volume. The sand particles in Rembrandt’s quartz grounds are very fine, with particles varying from approximately 5 to 60 µm and having sharp edges. Microscopic analysis revealed angular quartz particles and their sharp edges were indicative of recent mechanical grinding. This preparation provided a semi-translucent, textured surface ideal for enhancing the depth of painted layers.

The analysis of quartz grounds has identified trace amounts of magnesium, calcium, and occasionally sodium, lead, titanium, and manganese. These elements are primarily associated with the clay minerals surrounding the quartz particles. The detection of calcium suggests the inclusion of chalk, while the presence of lead indicates the addition of a drying agent to the ground mixture or the oil binder. Examination of the angular quartz particles reveals that they consist solely of silicon and oxygen (SiO₂). X-ray diffraction confirms that the quartz is alpha-silica, commonly known as ordinary sand.

The color of quartz grounds ranged from yellowish-brown to reddish, depending on the inclusion of pigments such as iron oxides and umber. This tonal variability reflects Rembrandt’s adaptability and his workshop’s experimentation with materials.

Viewed with transmitted light microscopy at 10x magnification, this sample showcases the stratified structure of quartz painting grounds. The interaction between light and the layers reveals details about the composition and preparation techniques used by artists.

Rembrandt, Civic Guardsmen of Amsterdam Under Command of Banninck Cocq, also known as The Night Watch, dated 1642, canvas, 363 x 438 cm, Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum

Key Takeaways for Artists

Quartz grounds offer a textured surface that interacts dynamically with painted layers.

Fine-grained sand improves the stability and durability of the ground.

Contrasting Dutch and Italian Grounds

While Dutch grounds prioritized functionality and tonal interplay, Italian artists favored smoother, highly absorbent gesso grounds. Italian panels often featured multiple layers of gypsum bound in animal glue, creating a reflective white surface ideal for meticulous underdrawing and glazing techniques. By contrast, Rembrandt’s middle-tone grounds were deliberately muted, allowing chiaroscuro effects to emerge more naturally without excessive underpainting.

Practical Lessons for Modern Artists

Experiment with Layering: The double-ground technique offers flexibility in achieving tonal depth, allowing for interplay between underlayers and painted details.

Leverage Texture: Incorporating quartz or sand into grounds adds dimension and provides a robust surface for heavy impasto.

Tailor the Tone: When choosing ground colors, consider the painting’s subject—darker tones suit portraits, while lighter hues enhance landscapes.

Reviving Historical Practices

Rembrandt’s mastery of grounds demonstrates their importance as more than a preparatory step. His ability to adapt materials and techniques to his artistic vision is a lesson in resourcefulness and innovation. By revisiting historical recipes and tailoring them to contemporary needs, today’s artists can achieve surfaces that support and enhance their creative expressions.

Bibliography

Groen, Karin. “Grounds in Rembrandt's Workshop and in Paintings by His Contemporaries.” Rijksmuseum Technical Bulletin, 2001.

Summary: Explores Rembrandt’s ground preparation techniques, analyzing materials such as lead white, umber, and quartz, and contrasting them with Italian methods.

Link: Link to Article.

De Mayerne, Theodore Turquet. Pictoria, Sculptoria et quae Subaltemarum Artium. 1620.

Summary: Provides detailed recipes for grounds, including the preparation of chalk-glue layers and double grounds for canvas and panel.

Beurs, Willem. The Large World of Small Painting. 1692.

Summary: A guide for artists, including practical advice on grounds and pigment mixtures for different types of paintings.

Bomford, David, et al. Art in the Making: Rembrandt. London: National Gallery, 1989.

Summary: Technical analyses of Rembrandt’s materials and methods, focusing on ground preparation and painting techniques.

Frequently Asked Questions About Painting Grounds

What is the purpose of a ground in painting?

What materials were used in Rembrandt's grounds?

Rembrandt's grounds often included a base layer of chalk or quartz mixed with clay, topped with pigments such as lead white, umber, or charcoal black. These materials were bound in glue or oil, depending on the support and desired texture.

How did the color of the ground affect Rembrandt's painting techniques?

The ground’s color influenced how light and shadow were established. Rembrandt often used middle-tone grounds, allowing for quick division of light and dark, enhancing chiaroscuro effects central to Baroque painting.

What are quartz grounds, and why did Rembrandt use them?

Quartz grounds, unique to Rembrandt's later works, contained finely ground sand mixed with clay minerals. They provided a durable, textured surface and contributed to the tonal depth of his paintings.

What is the difference between Dutch and Italian grounds?

Dutch grounds, like those used by Rembrandt, often employed thin chalk-glue layers with oil imprimatura for tonal depth. Italian grounds favored smoother, gesso-based layers suitable for detailed underdrawings and glazing.

How can modern artists apply Rembrandt’s ground techniques?

Modern artists can experiment with middle-tone grounds for tonal balance, incorporate textures like quartz for depth, and layer grounds to achieve specific effects inspired by Rembrandt’s techniques.

Why were double grounds significant in Rembrandt’s workshop?

Double grounds, featuring a reddish base and lighter topcoat, allowed for tonal flexibility and were extensively used in Rembrandt’s workshop to harmonize with the dramatic lighting of his compositions.

Are there durability concerns with certain types of grounds?

Grounds made solely with animal glue-based binders can flake or crack over time. Rembrandt mitigated these issues by using oil-bound grounds for flexibility and durability.