Simple Rules for Painting in Oils

The following is derived from Arthur Pilans Laurie's book, Simple Rules for Painting in Oils:

It is an old saying that rules are meant to be broken. No one did this more successfully than Rembrandt. For instance, the rich red in the tablecloth in the Syndics is obtained by glazing a translucent red over brown instead of over a brighter red. Rules are meant to be broken, but it is necessary to know them first.

Syndics of the Drapers' Guild, by Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, oil on canvas, 1662, 75 x 109 in. (1915 x 2790 mm), Rijksmuseum.

The following is based on Simple Rules of Painting in Oil by Arthur Pillans Laurie (1861–1949) and adapted for today's painters:

The difficulty in laying down rules for painting today is that no two painters paint alike. The old schools from the Renaissance built up a picture with a definite scheme based on studio experience. This tradition existed even in the eighteenth century. For instance, if we compare George Romney's early pictures, Romney having been taught by a peripatetic portrait painter, with many of the pictures of Sir Joshua Reynolds, who was always experimenting, we can see the values of such traditions as existed even then.

George Romney (self-portrait), by George Romney, oil on canvas, 1784, 49 1/2 in. x 39 in. (1257 mm x 991 mm), National Portrait Gallery.

General rules can be laid down:

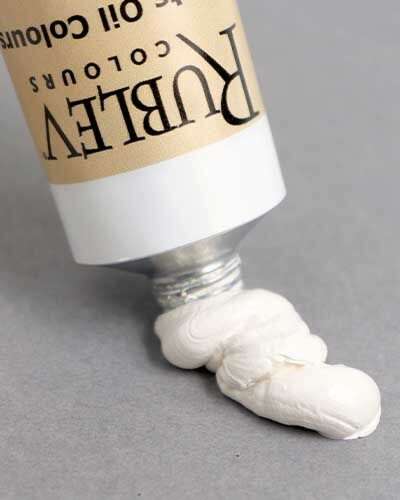

1. The priming should be white.

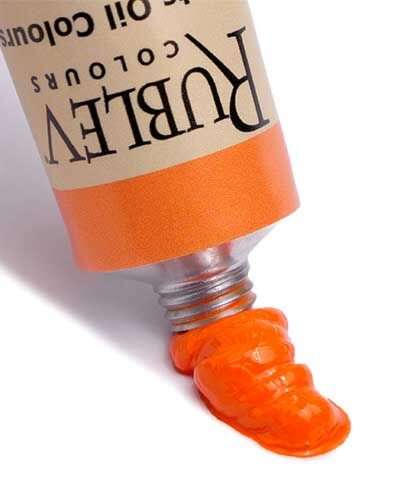

2. The first painting should be done with the most opaque pigments. Opaque pigments include Cerulean Blue, Chromium Oxide Green, Mars Yellow, Cadmium Yellows, Nickel Titanate Yellow, Red and Violet Hematite, Indian Red, Mars Red and Violet, Cadmium Reds, Mars Black, and Titanium Buff.

Next in order of opacity come the Cobalt Blues, Cobalt Greens, opaque Yellow Ocher, Chrome Yellows, Naples Yellows, Benzimidazalone Yellows and Oranges, opaque Red Ocher, Vermilion, Umbers, Bone or Ivory Black.

In the following list, we have translucent pigments: Ultramarine Blue, Prussian Blue, Lead-Tin Yellows, Arylide Yellows, and Raw and Burnt Siennas.

Still more transparent are the following pigments: Phthalocyanine Blues, Phthalocyanine Greens, Hanza Yellows, Azo Yellows, Diarylide Yellows, Alizarin Crimson, Madder Lake, Quinacridone Reds and Violets, Anthraquinone Reds, Carbazole Dioxazine Purples.

3. Translucent pigments only should be used for glazing or scumbling, adding Lead White for opacity when this quality is required.

4. When glazing is resorted to, the underlying solid color should be lighter than the glazing color.

5. Repainting should be as much as possible avoided. Direct, simple solid painting is best. Stiff oil paint laid thinly with no overpainting on a white or tinted ground retains its brilliance. For example, compare Turner's oil sketches with his elaborately finished pictures. Whistler painted thinly but with an excess of oil on dark backgrounds. His pictures could probably be recovered by exposure to north daylight.

6. As far as possible, a cross-section of the picture should go from dark to light.

7. Where this is impossible in painting highlights, an ample thickness of Lead White should be used. Adding Titanium White to Lead White may be used to obtain superior opacity and brightness.

8. Avoid excess oil and oleoresinous mediums.* Oil colors straight from the tube usually have sufficient or more than sufficient oil. A few exceptions are Ivory or Bone Blacks, Lamp Blacks, Alizarin Crimson or Madder Lake, most organic red and yellow pigments (Quinacridone, Pyrrole, Hansa, Azo, etc.), and Raw and Burnt Sienna. They may require a little oil to prevent cracking when used purely from the tube. Mixed together, bodied oil (stand oil) and solvents, such as odorless mineral spirits or turpentine, can be used when dilution is necessary.

9. Oiling out will result in darkening. If the picture has become matte in some places, try polishing it with a lint-free cloth. If oiling out must be resorted to, use the very minimum of oil, rubbing off all excess with a rag.

10. Use few colors in your pictures, and as far as possible, let these be among the opaque pigments. Apart from other reasons, it takes a lifetime to master the harmonies and decorative possibilities of some half dozen pigments.

11. Use Lead White and avoid Zinc White in oil painting. Add Titanium White for additional opacity in highlights, if required.

12. Regard an oil painting as if it consisted of a series of colored films which will become more translucent and yellow with age.

A Few More Rules

Several more rules should be added to the list created by A.P. Laurie. These are not found in his list because they were not well understood when he wrote them. These rules are perhaps the most important in painting, as conservation research in the latter half of the twentieth century clearly identifies.

1. Paint on rigid supports using materials that are least responsive to changes in the environment caused by fluctuations in relative humidity and temperature.

2. Where this is not possible, protect the support, such as a wooden panel, and especially flexible supports, such as a stretched canvas, from the environment on all sides by framing the picture and using a protective backing.

To learn more about these rules, please refer to the following article: Why Canvas is not the Best Choice for Painting.

3. Underlying paint layers must be hard dry before applying the next layer over it. A "hard dry" paint film is distinguished from one that is "touch dry" by being dry (polymerized) all the way through the entire paint layer. This is important to avoid cracking and alligatoring paint.

For more information on this rule, please read Fat Over Lean—A Basic Rule in Painting.

A Word About Lead White

Many readers may wonder why these rules not only include the use of Lead White but advocate its use in oil painting. Although many painters today refuse to use Lead White in their pictures due to concerns about its toxicity, the importance of this pigment in oil painting has been intensely studied for over a hundred years. The majority of conservators and scientists conclude from these studies that it is the only pigment that stabilizes the polymer network formed by drying oils; hence is essential for the longevity of oil paintings.

Notes

* Oleoresinous mediums consist of natural or synthetic resins with a drying oil and often a solvent and other additives, whether homemade or as commercial products. Examples of homemade oleoresinous mediums are the preparations recommended by Ralph Mayer in The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques of one-third dammar varnish, one-third turpentine, and one-third bodied oil (stand oil). Commercial products include alkyd mediums, megilps, Maroger Medium, Roberson's Medium, etc. For more information, please read Should Oil Painters Use Resin-Based Mediums such as Dammar and Maroger?

References

Arthur Pillans Laurie, The Painter's Methods and Materials, 1926.

Arthur Pillans Laurie, Simple Rules for Painting in Oil, 1932.

Arthur Pillans Laurie, New Light on Old Masters, Sheldon Press, 1935.

Learn More

The principles behind these rules are fully explained in Painting Best Practices online course website. Please visit PaintingBestPractices.com for more information.